Captioning Sound Effects in TV and Movies

The first electric television was invented in 1927. 44 years later, captions were introduced to TV programs.

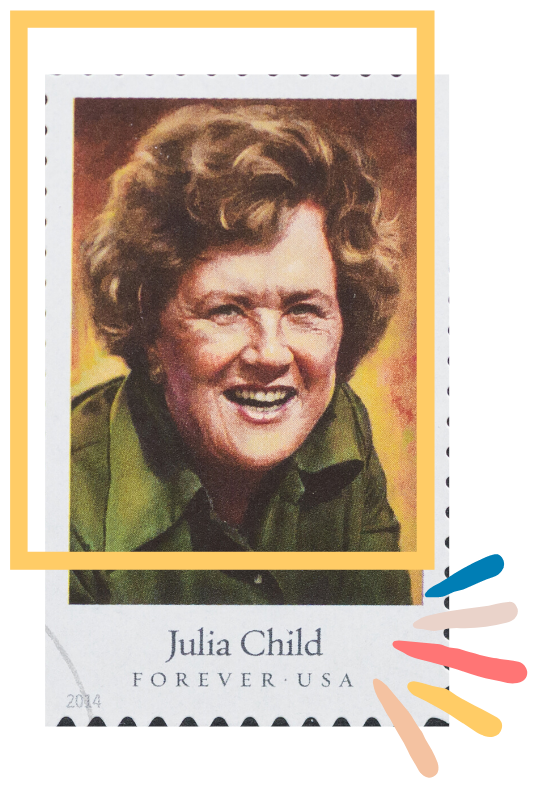

In 1972, Gallaudet University, American Broadcasting Company (ABC), and the National Bureau of Standards presented the technology needed to make television shows accessible with captions. The first program to officially broadcast with captions was “The French Chef” with Julia Child, airing across the U.S. on PBS.

Since then, captions have become a legal mandate for broadcast media and an integral part of the enjoyment of media and entertainment.

Captioning Best Practices for Media and Entertainment

What are Captions?

Captions are a textual representation of the audio within a media file. They make video, like TV shows and movies, accessible to the deaf and hard of hearing communities by providing a time-to-text track as a supplement to, or as a substitute for, the audio.

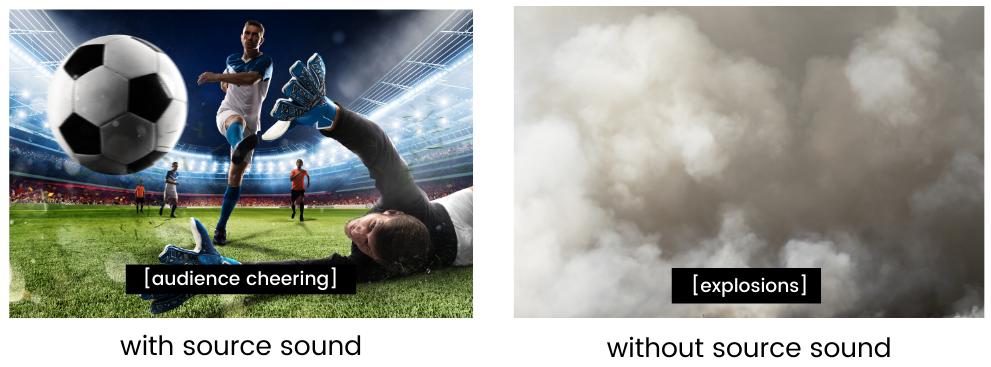

While the text in a caption file mostly contains speech, captions also include non-speech elements like speaker IDs and sound effects that are critical to understanding the plot.

In many parts of the world, captions and subtitles are used interchangeably – like in countries in Europe or in Latin America. However, in the United States, there’s a clear distinction between captions and subtitles.

Captions assume the viewer cannot hear and they are often dictated with a “CC” icon on video players or remotes. On the other hand, subtitles are for hearing viewers who don’t understand the language of the show or film. Unlike captions, subtitles don’t include the non-speech elements of the audio.

In the next section, we’ll dive into how to caption sound effects, a non-speech element and an important component of captions.

Captioning Sound Effects

The Described and Captioned Media Program (DCMP) is funded by the U.S. Department of Education and administered by the National Association of the Deaf. Their mission is to “promote and provide equal access to communication and learning through described and captioned educational media.”

The DCMP provides a set of guidelines on captioning best practices. One guideline in particular touches upon caption quality. It states that captions should be accurate, consistent, clear, readable, and equal. Under the “clear” section, it specifically states that captions need to be a complete textual representation of the audio, including non-speech information, in order to provide clarity.

According to the DCMP, sound effects are sounds in a TV program or film other than music, narration, or dialogue. Sound effects are captioned if it’s necessary for understanding and/or enjoyment of the media.

When it comes to sound effects, there are a number of best practices to keep in mind as to not distract or disrupt the viewing experience for viewers. Let’s jump in!

Captioning Best Practices for Media and Entertainment ➡️

- For example, it’s not necessary to caption a driving car if it has nothing to do with the plot, but if an important character drives into the driveway and it plays into the plot, it should be captioned

For more information on captioning sound effects and other non-speech elements, visit the DCMP website.

Legal Requirements for Captioning TV and Movies

Aside from enhancing the viewer experience, broadcast media companies caption their media to comply with the FCC.

The Federal Communications Commission, otherwise known as the FCC, regulates interstate and international communications, including in the analog and digital spaces.

Closed captioning was mandated by the FCC in the early 1980s as a requirement for broadcast TV to make it accessible to all audiences, including people with hearing loss. There are about 466 million people with hearing loss worldwide according to the World Health Organization, and when media is not captioned, millions of people cannot access and enjoy media.

Now that online video is becoming increasingly popular, the 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act (CVAA) was enacted to ensure that online video content is made accessible.

Under the CVAA, all online videos that previously aired on TV in the U.S. with captions must include captions when published on the internet. This includes clips and montages.

In order to comply with the law, TV and movie broadcasters must ensure that they provide captions for their media and that non-speech elements, like sound effects, are captioned as well.

![doorbell ringing. Repeated words: [doorbell ringing] ding, ding Two different words: [doorbell ringing] ding-dong](https://www.3playmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/Copy-of-sound-effect-images-9.png)

![Sustained sound: [dog barking] woof, woof...woof Abrupt sound: [dog barks] woof](https://www.3playmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/Copy-of-sound-effect-images-11.png)

![Slow: [clock chiming] dong...dong...dong Fast: [gun firing] bang, bang, bang](https://www.3playmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/sound-effect-images-1.png)