UK Subtitle Regulations for Television & Broadcast Media

Updated: June 3, 2019

We’ve covered the various disability laws and FCC mandates that require closed captioning for video in the US, as well as how the AODA affects subtitling in Ontario, Canada.

The United Kingdom has its own rules and regulations around subtitles for television and other broadcast media. Here’s an overview of the major laws, codes, and recommendations for subtitles in the UK.

Broadcasting Act of 1990, Section 35

British parliament passed the first piece of subtitle legislation in 1990: the Broadcasting Act.

The act required public broadcasting stations to “provide minimum amounts of subtitling for deaf and hard-of-hearing people and to attain such technical standards in the provision of subtitling as the ITC specifies.” ITC is a Technical Performance Code that governs technical standards for subtitles. The current UK standard for subtitle transmissions via teletext is ITU-R (CCIR) Teletext System B.

Although the Broadcasting Act is viewed as largely deregulating British broadcasting, the inclusion of subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing is a welcome redeeming factor.

Communications Act of 2003

In 2003, British parliament overrode the Telecommunications Act of 1984 and replaced it with the Communications Act. This act consolidated regulatory authority of telecommunications and media within the Office of Communications (Ofcom).

In contrast to the Broadcasting Act, the Communications Act introduced sweeping regulations. For example, the act made it illegal to steal your neighbor’s Wi-Fi connection, or to stalk and harass people online.

The Communications Act expanded requirements for UK broadcasters to provide ‘television access services,’ like subtitling, sign language, and audio descriptors. These new provisions are specified, reviewed, and enforced by Ofcom.

Ofcom

Ofcom was created in 2002 by the Office of Communications Act, but was granted full regulatory authority the following year by the Communications Act. Like the US’s FCC, Ofcom presides over licensing, policies, complaints, and protections in telecommunication and broadcasting.

All commercial television and radio broadcasts in the UK are licensed by Ofcom and are therefore subject to its regulations. Viewers can submit grievances to Ofcom, who will investigate whether or not the broadcaster violates the Broadcasting Code and take appropriate recourse.

In a May 2013 study with Action on Hearing Loss, Ofcom found that:

- 67% of people with hearing loss said that TV is important to them.

- People with hearing loss watch TV for an average of 4.3 hours a day.

- 7.5 million people have used subtitles to watch television, although six million of them do not have hearing loss.

- Nearly half of respondents with moderate hearing loss use subtitles, rising to 73% for those who are profoundly or severely deaf.

- Around 70% of those with hearing loss agreed that pre-recorded and live subtitling is significantly helpful.

With data to back their cause, Ofcom strives to raise awareness of the benefits of subtitles and puts pressure on channels within their jurisdiction to add subtitles to their programming.

Section 303

Section 303 of the Communications Act is titled “code relating to provision for the deaf and visually impaired.” It achieves two things:

- It charges Ofcom with devising and updating an official code that outlines accessibility requirements for broadcasters.

- It standardizes deadlines for ascending degrees of compliance.

For more clarity on how these subtitling regulations work, let’s look at the Ofcom codes in more detail.

Ofcom’s Code of Guidance on Standards for Subtitling

In a Forward, this code explains what makes subtitling such a unique communication challenge and why it is so important.

This code gives very specific parameters for recommended subtitle formatting, display, and quality for British television. Requirements include:

- Adding speaker IDs

- Denoting off-screen voices

- Preserving the tone of original speech (ex., adding question marks, exclamation points, or ellipses)

- Clean-read instead of verbatim transcription (ex., eliminating ‘um’s, stutters, and backtracking)

- Sound effects

- Color-contrast of text on the screen

- ‘#’ symbol to denote music or song lyrics

- Bracketed descriptions of speech style (ex., (SLURRED) What are you looking at?)

- Bracketed text to denote whispered speech (ex., (Are you sure about this?))

Digital Terrestrial Television (DTTV)

Digital Terrestrial Television has its own set of rules for subtitling. Here are a few of them:

- Tiresias font, a standard Sans Serif, is required for all subtitles.

- Font size is standardized base on the capital ‘V’ being 24 television lines high.

- A range of 12 colors is allowed approximate the colors of teletext subtitles.

- Line breaks on conventional aspect ratio receivers (4:3) and widescreen (16:9) receivers must retain the original emphasis of the subtitle.

- Subtitles should be placed in the Safe Caption Area of a 14:9 display.

- To indicate music, use two semi-quavers instead of the usual ‘#’ symbol.

- Italics may be used to add emphasis.

“Losing subtitles is as frustrating for the hearing-impaired viewer as losing sound is for the hearing viewer.”

Subtitle Errors

Ofcom officially requires broadcasters to issue an apology if subtitles fail:

Ofcom’s Code on Television Access Services

The most current version of this code was published in December 2012, and can be found on the web here.

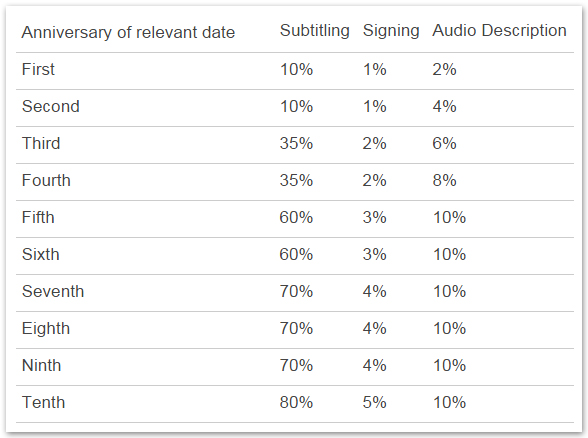

This code sets the specific requirements for subtitling, sign language, and audio description for licensed television broadcasters. Broadcasters need to reach certain accessibility milestones 5 years and 10 years after the ‘relevant date’: 60% of all programming must be subtitled by year 5, and 80% must be subtitled by year 10. Unless otherwise specified, the ‘relevant date’ is the first date of licensed broadcasting.

Yearly benchmarks are set in the interim. The exact dates and requirements vary slightly by channel, and the BBC has set their own timetable. For all others, the timeline looks like this:

To Whom Does This Code Apply?

This code applies to:

- Licensed public service channels

- Digital television program services

- Television licensable content services (TLCS)

- Restricted television services

- Digital television program services (DPS) provided by the Welsh Authority (including S4C Digital)

Exceptions

Ofcom can exempt certain programs from the subtitling requirement based on the following factors:

- The degree to which disabled people will benefit from accessible services

- Size of the intended audience

- Number of people in audience who would benefit from accessible services

- Whether intended audience is within the United Kingdom

- Degree of technical difficulty

- Cost of subtitling, relative to the above factors

Authority for Television on Demand (ATVOD)

The Authority for Television On Demand (ATVOD) is an independent co-regulator for video on demand in the UK. In September, 2012, the ATVOD consulted with disability experts and media industry professionals to produce Best Practice Guidelines for access services for video on demand. The full PDF can be found on the web here.

Pages 6-8 address subtitling best practices. After reviewing the definition of subtitles and who benefits from them, the guide makes an interesting recommendation for how to prioritize subtitling certain programs:

The guide drills into the details of subtitle placement on screen, illumination and color-contrast of font, and synchronization with the spoken text. It recommends target speed of subtitle display and transition (160-180 words per minute), with the exception of subtitles aimed at a young audience:

This is an intriguing exception to the recommendation for maximum accuracy: subtitles can be edited to be more easily understandable by children, so long as the original meaning and intent is preserved.

—

To learn more about UK subtitle regulations and disability laws, download this free whitepaper.